New Documentary ‘Last King of Queensland’ Examines Joh’s Legacy

By: Justin Rouillon

I moved back to Queensland in December, 1987. For five years my family had been living on the mid-north coast of New South Wales, and we arrived back to a state in turmoil.

Even as a 10-year-old schoolboy, I could appreciate the gravitas of Queensland’s longest serving premier being unceremoniously dumped, after the revelation that corruption was systemic within his government and his police force.

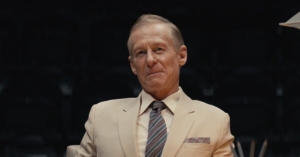

The new feature-length documentary ‘Joh: Last King of Queensland’ is streaming now on Stan, with one of Australia’s most controversial political figures being brought to life by director Kriv Stenders (Red Dog, The Correspondent, The Go-Betweens: Right Here) and actor Richard Roxburgh (Moulin Rouge!, Elvis, Rake).

Stenders, along with investigative journalist Matthew Condon, (whose own true crime trilogy Three Crooked Kings, covers in detail police and government corruption in Queensland) puts Joh’s legacy under the microscope with a diverse range of voices from across the political and social landscape.

Richard Roxburgh does a superb job of portraying Joh Bjelke-Petersen in his tumultuous final days in office – when he famously locked himself in his office for three days, refusing to engage with his party, Parliament, or the press in a desperate bid to cling on to power. Joh even attempted to contact Buckingham Palace, reportedly trying to speak directly to the Queen in a bid to have the Queensland Parliament dissolved.

From federal National’s leader David Littleproud and former government colleague Bob Katter, to journalists, musicians and Joh’s own children, the documentary paints a picture of a leader who was either loved or loathed.

There was no middle ground with Joh Bjelke-Petersen; immensely popular and widely loved with his conservative base, he essentially went to war with those he saw as his political enemies, or those he saw as not fitting into his vision for Queensland.

Trade unionists, students, musicians and first nations peoples were all in the firing line, with Bjelke-Petersen also playing a not insignificant role in the dismissal of the Whitlam Government in 1975.

Born to a devout Danish Lutheran family (his father Carl was a Lutheran pastor), and raised on a farm in Kingaroy, Bjelke-Petersen was first elected to the Queensland Parliament in 1947. He would eventually work his way through the ranks of the Country Party (now the Nationals), becoming State Premier in 1968.

He stayed in the top job for just shy of two decades, helped in part by what became known as the Bjelke-mander; a malapportioned electoral system that gave much more voting power to rural and regional areas, where the National Party had strong support.

A vote in a remote or rural seat could be worth two to three times more than a vote in an inner-city seat, because a rural electorate might have 10,000 voters, while a city seat could have three or four times that number, but each would elect one MP.

And while there’s no argument that Joh was good for business and the economic development of Queensland, it came at a huge social cost.

He ran things like a police state, famously declaring a state of emergency during the 1971 Springboks rugby tour, with anti-apartheid protesters being violently dispersed, beaten, or arrested by police.

In 1977, Joh effectively banned protest saying, “The day of the political street march is over. Don’t bother applying for a permit. You won’t get one. That’s government policy now!”

Throughout his tenure, it was progress at all costs, with many of Queensland’s heritage buildings being demolished in the middle of the night, as was the case with Brisbane’s iconic ballroom Cloudland in November 1982.

Throughout the late 70s and early 80s, suburban concerts were a favourite target of police raids, with that period seeing a virtual exodus of Brisbane’s creatives and musicians to interstate or overseas.

The most famous of these were The Go-Betweens and The Saints, with members of both groups appearing in Last King of Queensland.

Ultimately, it was an iconic piece of investigative journalism that saw Joh’s house of cards collapse, with Chris Masters’ 1987 expose ‘The Moonlight State’ uncovering systemic and widespread corruption throughout the Queensland Police and State Government.

This corruption, nicknamed ‘The Joke’, saw both police and government ministers benefiting from organised crime – prostitution, illegal gaming and casinos and drug trafficking.

The subsequent Fitzgerald Inquiry which investigated systemic corruption in the police and politics, would be the downfall of Joh, and end the decades long rule of the National Party in Queensland.

It would also see former government ministers serve jail time, as well as the former Police Commissioner Terry Lewis, who was stripped of his knighthood and sentenced to 14 years in prison for corruption.

It should be noted that Joh was never convicted of official corruption, although did stand trial in 1991 for perjury as a result of his testimony during the Fitzgerald Inquiry.

That trial was controversially thrown out of court, when it was discovered that the jury foreman was a member of the Young Nationals, as well as the ‘Friends of Joh’ movement.

Due to his age (then 81) and declining health, a retrial was not pursued.

Joh: Last King of Queensland is an extraordinary insight into Queensland during an infamous period, and essential viewing if you have an interest in Australian history, politics, or have big questions about power, democracy, and what Queensland once was.

You can stream Joh: Last King of Queensland on Stan now.

Article supplied with thanks to 96five.

Feature image: Publicity Images Supplied by Stan